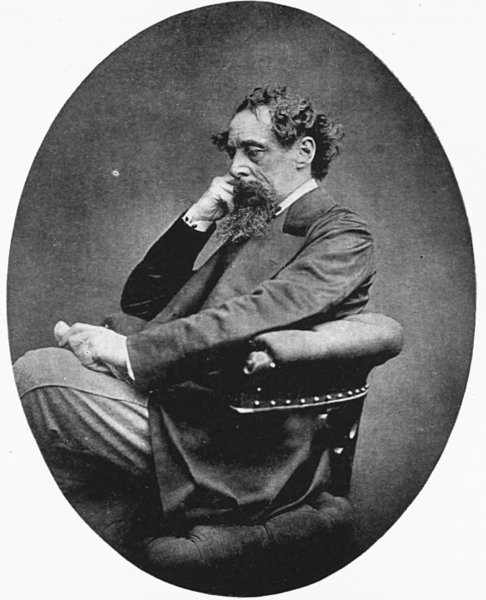

If you are a regular reader, you will know that Charles Dickens is my second favourite author, after Jane Austen of course! I have been lucky to spend a lot of time in Kent on holidays, immersing myself in the county that meant to much to Dickens, where he often found himself the happiest. Despite this, it was also scene of one of his most traumatic experiences in his life, the Staplehurst train crash of Friday 9th June 1865. It is this horrendous event that would play on Dickens for the last five years of his life.

On that day, Charles Dickens was returning from a holiday in Paris with his mistress, Ellen Ternan (you can find a blog post I wrote about her here), and Ellen’s mother. Their relationship was a huge secret, despite it being public that Dickens had separated from his wife, Catherine. The train that the party were taking to London was known as a tidal train, a train that was used by passengers also using ferries to take them between London and the continent, via Kent.[1] There was no warning as to what lay ahead as repairs were being made to a bridge over the River Beault near Staplehurst, nine miles away from Maidstone.

The bridge in question was made from a mixture of cast iron, brick and timber. The reason for the repairs was because the timbers were prone to rotting due to exposure, meaning they had to replaced every so often. This was what was being done at the time of the crash, creating a 42 feet gap that workers were working on replacing.[2] Unlike now, there were no safety measures in place for trackside workers, or systems to easily monitor where trains were. This is what made this situation a highly dangerous one.

The foreman in charge was Henry Benge, who had worked on the railway for many years with no issue prior to the crash at Staplehurst. His trustworthiness had been the reason why he had been promoted to the foreman. As soon as the scheduled 2:45pm train had passed, Benge announced to his team that it would now be safe to start taking the tracks on the bridge up, for the tidal train wasn’t due until 5:24pm. That would be plenty of time to get the work done.[3] However, Benge had read this time from the Saturday timetable, not the Friday one. The tidal train was in fact due at 3:19pm.[4]

Without realising this error, the team set to work. A man was sent further down the tracks with red flags to wave as a warning to stop at any possible train coming. He was also given what was known as fog signals, small detonator type things that would make a noise if a train ran over them, alerting a driver to danger ahead. These signals were never used, for the man in charge of them thought they were meant for foggy weather, not as a warning signal. He was also not as far down the track as he had been instructed to be, meaning that when the tidal train came, the driver only had just over 500 feet to stop in.[5] With such a long train and the momentum, this was impossible, despite whistling twice to alert the brakemen to apply the brakes.

When the train reached the bridge, the engine and the first few carriages had managed to bridge the gap by sheer momentum. The rest, other than a few towards the rear of the train, ended up in the river bed. The only first class carriage to bridge the gap was the one that Charles Dickens was in, albeit derailed at a slight angle.[6] Ellen was the only one of the party to receive minor injuries, meaning they were able to get out of the carriage safely.

The horror that they saw was unimaginable. As Dickens himself would later recall, ‘no imagination can conceive the ruin of the carriages, or the extraordinary weight under which the people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among iron and wood, mud and water.’[7] Still, Dickens did what he could to help those dying and injured over the next three hours whilst waiting for help to come. He retrieved a flask of brandy he’d been travelling to offer around, as well as filling his top hat with water. One injured woman he offered his brandy to was dead within minutes of partaking.[8]

In total, ten people died and forty were injured in the crash. People had to be held accountable for this disaster. Harry Benge, the foreman, and his supervisor, Joseph Gallimore, were charged with manslaughter. At trial, Gallimore was acquitted, with Benge receiving nine months imprisonment. Upon release, he worked as a farm labourer, until the guilt of what happened at Staplehurst made him mad. He died in the Kent County Asylum in 1905.[9] The train driver, whilst not responsible for the accident, was dismissed for it was claimed he could have seen the red flags before he had done.[10]

Dickens himself didn’t immediately noticed the effects it would have on him mentally, but they would be significant. When help did arrive, he remembered that a working copy of the latest instalment of Our Mutual Friend was still in the train carriage.[11] He managed to retrieve it before leaving for London. It was only the day after, when he was back home at Gads Hill Place, just three miles outside of Rochester in Kent. It was then he told the landlord of the village pub that he ‘never thought I should be here again’.[12] It was obvious the trauma was starting to set in. In fact, it would stay with him until he died five years later, on the fifth anniversary of the crash, 9th June 1870. Charley, Dickens’ eldest son, commented that his father ‘may be said never to have altogether recovered’, for he often had panic attacks and was scared to travel afterwards.[13] We would now recognise that Dickens was suffering from a form of post-traumatic stress disorder, which probably did help to contribute to his continual overwork and death.

A year after the crash, Dickens produced The Signalman (1866), a ghostly short story that may not have been produced without the events of the Staplehurst crash. It tells the story of a signalman who works at a remote signal box near the opening of a tunnel. He is visited by a traveller, whom the signalman shares about a ghostly apparition he has seen prior to bad accidents. The story reflects Dickens’ own helplessness in saving people’s lives, despite his best efforts, just as had happened at the crash site.[14]

The Signalman is actually one of Dickens best ghost stories and captures the concept of internal turmoil and possible mental health issues very well. It is obvious how Dickens own experiences influenced this story, just as with much of his other writings, but it reinforces the idea of this fairly new transport being incredibly dangerous for staff and passengers alike. I hope you have a chance to read it within the context that Dickens wrote it, whilst remembering the other victims of the Staplehurst train crash.

[1] The Charles Dickens Page, ‘Charles Dickens, Henry Benge, and the Great Staplehurst Railway Crash’, https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/staplehurst-railway-crash-1865.html

[2] Charles Dickens Info, ‘Charles Dickens and the Staplehurst Railway Accident’, https://www.charlesdickensinfo.com/life/staplehurst-railway-accident/

[3] The Charles Dickens Page, ‘Charles Dickens, Henry Benge, and the Great Staplehurst Railway Crash’

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Charles Dickens Info, ‘Charles Dickens and the Staplehurst Railway Accident’

[7] Charles Dickens quoted in The Charles Dickens Page, ‘Charles Dickens, Henry Benge, and the Great Staplehurst Railway Crash’

[8] Charles Dickens Info, ‘Charles Dickens and the Staplehurst Railway Accident’

[9] The Charles Dickens Page, ‘Charles Dickens, Henry Benge, and the Great Staplehurst Railway Crash’

[10] Ibid

[11] Charles Dickens Info, ‘Charles Dickens and the Staplehurst Railway Accident’

[12] University College Santa Cruz, ‘The Staplehurst Disaster, 9th June 1865’, https://omf.ucsc.edu/dickens/staplehurst-disaster.html

[13] Ibid

[14] Oldstyle Tales Press, ‘Charles Dickens’ The Signal-Man: A Detailed Summary and a Literary Analysis’, 20 November 2018, https://www.oldstyletales.com/single-post/2018/11/20/charles-dickens-the-signal-man-a-two-minute-analysis-of-the-classic-ghost-story

Thank you. Great post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A really good piece Danielle – thank you – I read ‘The Signalman’ for GCE O Level English in about 1976 and it is still probably my favourite ghost story. Frederick Forsyth’s ‘ The Shepherd’ is also very good though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, thank you! I knew Dickens had been involved in a train crash and love The Signalman, but had never made the connection. I shall listen to it again (there’s a wonderful version of it narrated by Sam Mendes) with that in mind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must admit, as much as I know of Dickens, including the crash and the Signalman, I never really put the two together until recently. There was a very interesting documentary on Sky at Christmas about Dickens and his ghost stories and the connection was made on that. A bit of a revelation!

LikeLiked by 1 person